The Truth About Agent Orange and Other Herbicides in Thailand During the Vietnam War

CCK Law: Our Vital Role in Veterans Law

VA’s Herbicide Problem

Introduction:

Agent Orange is an herbicide that was used by the United States during the Vietnam War. Agent Orange was made up of 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T. Its contaminant TCDD is a highly toxic byproduct of producing Agent Orange.

VA’s regulation 38 C.F.R. 3.307 defines herbicide agents as 2,4-D; 2,4,5-T and its contaminant TCDD (also known as dioxin), cacodylic acid, and picloram. Agent Orange is just one of the “rainbow herbicides” that the United States used. They also employed Agent Blue and Agent White, among many others.

The military used herbicides to clear foliage from the jungles and base camps of Vietnam. The heavy foliage provided excellent cover for the enemy. Herbicides were also used to kill crops to diminish the enemy’s food supply.

Exposure to these herbicides was later determined to pose a health risk to service members. Because of these risks, Congress eventually enacted laws providing benefits to those who were exposed if they subsequently developed certain diseases associated with the exposure. Because of the impossibility of determining which service members were exposed to what levels of toxicity, Congress decided that veterans who served in Vietnam would be presumed exposed to the harmful herbicides. Likewise, if a veteran were then diagnosed with certain diseases, the government would concede that the disease was related to the exposure. These presumptions result in the award of VA benefits, such as disability compensation, health care, etc.

When Congress enacted these laws, it did not limit potential benefits to those veterans who served in Vietnam. If a veteran served in an area other than Vietnam, such as Thailand or Korea, but was nonetheless exposed to the same herbicide agent as used in Vietnam, then they were to be awarded the same benefits as would a Vietnam veteran for the diseases associated with such exposure.

However, at that time, if the veteran did not serve in Vietnam, VA regulations provided no presumption of exposure for that veteran. Instead, the law mandated that a veteran show as a factual matter that they were as likely as not exposed to an herbicide agent like those used in Vietnam.

With those mandates, VA instituted a systematic process that restricts the law and ensures that otherwise qualifying veterans and their families are denied benefits. VA should afford the same presumption of exposure to Thailand veterans that it affords to Vietnam veterans because the same herbicides agents were used in Thailand.

However, as of the passage of the 2022 Honoring Our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act on August 10, 2022, VA has officially established a Thailand presumption for veterans. Now, veterans who served at any U.S. or Thai base from January 9, 1962 to June 30 1976, without regard to the Veteran’s MOS or where on base they were located, are eligible for presumptive service connection.

A. The legal framework of the Vietnam presumptions.

In 1991, Congress passed the Agent Orange Act, which mandated that certain diseases associated with exposure to herbicide agents, including chloracne and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, be presumed service-connected. Section 1116 of title 38 of the United States Code and 38 C.F.R. § 3.307 and 3.309 provide the legal authority and framework for awarding benefits to Vietnam veterans with herbicide agent-related diseases.

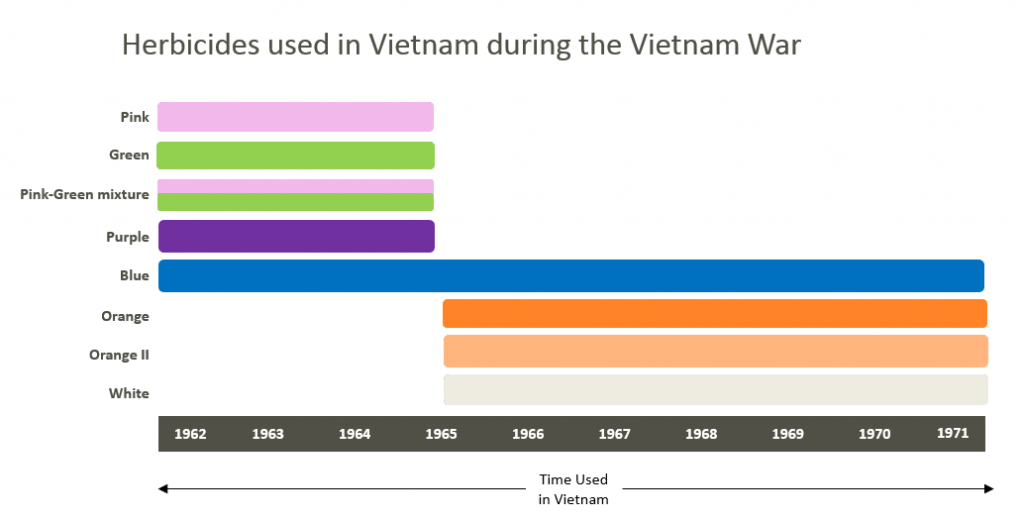

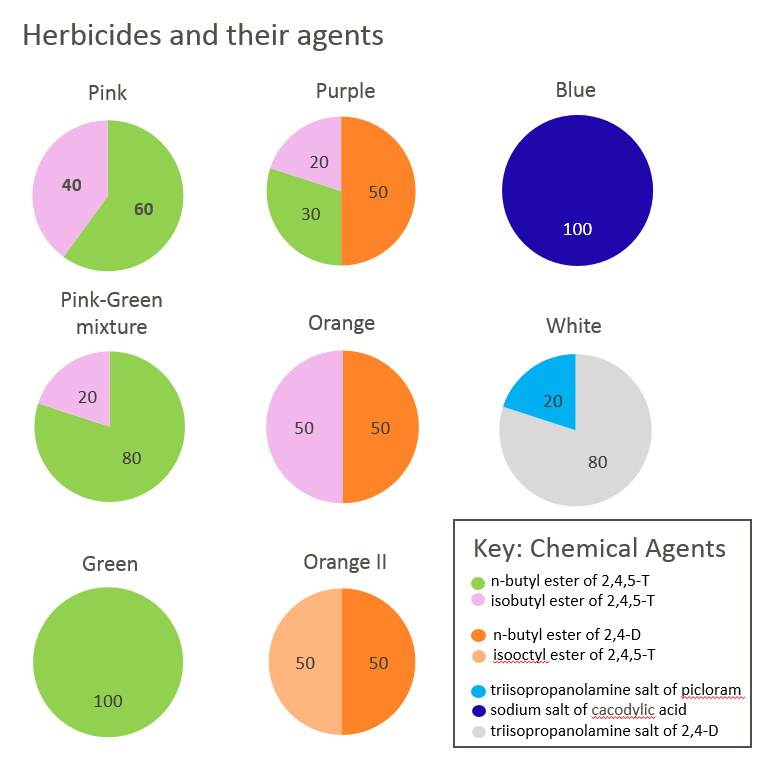

When Congress enacted this law, it stated that “the term ‘herbicide agent’ means a chemical in an herbicide used in support of the United States and allied military operations in the Republic of Vietnam during the period beginning on January 9, 1962 and ending on May 7, 1975.” 38 U.S.C. § 1116. Figure 1.1 lists (and Figure 1.2 illustrates) the chemical composition of each of the herbicide agents as well as the time period in which they were used in Vietnam.

VA 38 U.S.C. § 1116 is a dual-function statute titled: “Presumptions of service connection for diseases associated with exposure to certain herbicide agents; presumption of exposure for veterans who served in the Republic of Vietnam.”

| Code/Name | Primary Agents in Herbicide | Time Used in Vietnam |

| Pink | 60% n-butyl ester of 2,4,5-T 40% isobutyl ester of 2,4,5-T | 1962-1965 |

| Green | 100% n-butyl ester of 2,4,5-T | 1962-1965 |

| Pink-Green mixture | 80% n-butyl ester of 2,4,5-T 20% isobutyl ester of 2,4,5-T | 1962-1965 |

| Purple | 50% n-butyl ester of 2,4-D 30% n-butyl ester of 2,4,5-T 20% isobutyl ester of 2,4,5-T | 1962-1965 |

| Blue | 100% sodium salt of cacodylic acid | 1962-1971 |

| Orange | 50% n-butyl ester of 2,4-D 50% n-butyl ester of 2,4,5-T | 1965 and after |

| Orange II | 50% n-butyl ester of 2,4-D 50% isooctyl ester of 2,4,5-T | 1965 and after |

| White | 80% triisopropanolamine salt of 2,4-D 20% triisopropanolamine salt of picloram | 1965 and after |

VA followed suit by drafting regulations to coincide with the statute by defining the term as follows: “‘herbicide agent’ means a chemical in an herbicide used in support of the United States and allied military operations in the Republic of Vietnam[,] . . . specifically: 2,4-D; 2,4,5-T and its contaminant TCDD; cacodylic acid; and picloram.” 38 C.F.R. § 3.307(a)(6)(i).

B. The military used the same herbicides in Thailand that were used in Vietnam.

1. The Rules of Engagement for Vietnam and Thailand were similar.

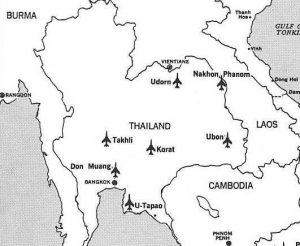

Both Vietnam and Thailand were engagement zones for deployed military personnel, and both countries had similar Rules of Engagement (Rules). Although most of the Air Force bases in Thailand were seen as staging hubs for operations within Vietnam, military personnel located throughout Thailand were also subjected to hostile attacks from Communists.

In the 1968 Contemporary Historical Examination of Current Operation (CHECO) Project Southeast Asia Report: Attack on Udorn, the Air Force recognized that Thailand was a “prime target of Communist expansion, and the interest of the Communists was intensified by the USAF presence.” The report also noted that there were an estimated 15,500 Communist insurgents and sympathizers in Thailand. From 1965 to 1968, 5,727 Communist insurgents in Thailand were either killed, arrested, or surrendered. From 1966 to mid-1968, insurgents conducted 331 assassinations and 1,087 armed encounters. The threats toward Air Force bases were legitimate and a serious concern for military units stationed in Thailand.

Bases in Thailand, including Korat, Nakhon Phanom (NKP), Ubon, Udorn, and U-Tapao, were subjected to sniper fire, perimeter penetration, and sapper (combat engineer) attacks. These attacks resulted in both U.S. and enemy causalities. The Department of Defense had legitimate concerns about the threat to U.S. personnel and equipment, which led to the decision to use herbicides within base perimeters as a means of preventing ambushes in Thailand.6

The similarities between base defense in Vietnam and Thailand were highlighted in the 1969 CHECO Report titled “7AF com Base Defense Operations: July 1965 – December 1968.” This report provides a general analysis of Air Force base operations. The report recognizes the heightened risk of attacks directed against air bases because they presented the enemy with a “concentration of lucrative targets.” Additionally, the report states: “Thailand is going through the same type of growing pains experienced in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), but the knowledge and experience gained in the development of air base defense in RVN permit a more rapid evolution in Thailand.” Thus, similar tactics and procedures in base defense were used in both Thailand and Vietnam because the bases were facing the same threat with similar resources.

The Rules provided authorization for, and limits on, the employment of herbicides throughout the Southeast Asian conflict. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) Directive 525-1 (1966) highlighted the procedure for requesting aerial spray, power spray, and hand spray in Vietnam. The directive empowered the Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (COMUSMAV), and the U.S. Ambassador to authorize herbicide operations. The directive delegated authority to approve defoliation requests using hand spray and ground-based power spray methods. The directive highlights U.S. assistance to com government in requesting, supplying, and planning defoliation operations.

2. Thailand’s strong connection to Operation RANCH HAND demonstrates that its bases received a steady supply of herbicides.

Similarities between the Rules in Thailand and Vietnam were also necessary due to Operation RANCH HAND activities in Thailand. Throughout the Vietnam War, RANCH HAND aircraft utilized bases in Thailand. Aircraft used for RANCH HAND, UC-123Ks, launched from airbases in Thailand including Ubon, Udorn, NKP, and Takhli on numerous occasions to conduct missions against targets in Vietnam and Laos.

In August 1963, the government of Thailand requested aerial spraying services from RANCH HAND aircraft to assist with its locust problem. From December 29, 1968, to January 2, 1969, RANCH HAND aircraft flew Agent Orange missions out of Udorn. On January 17, 1969, seven RANCH HAND aircraft flew to Ubon to conduct an attack the next day against a special target in Laos. From February 2 to 5, 1969, RANCH HAND flew Laos missions from Udorn. Udorn was again utilized August 31, 1969 to conduct an operation in which RANCH HAND aircraft flew 28 sorties from Thailand to target Laotian crops with Agent Blue using five UC-123s during a seven-day period.

Records from the Ranch Hand History Project show that Sergeant Richard E. Wolf, who worked on Operation RANCH HAND, received a letter of commendation for his actions in Thailand during these operations. National Archive records also reveal that herbicide missions launched from Thailand on July 6, 1966, August 29, 1966, December 15, 1967, June 7, 1967, April 18, 1969, and March 25, 1970. Although these missions were classified, they demonstrate the robust relationship between U.S. military in Thailand and Operation RANCH HAND.

Air Force documents confirm that herbicide deliveries not associated with RANCH HAND were transported to and from Thailand. National Archives records reveal that herbicides were transported from Vietnam to Takhli on April 7, 1973. Moreover, the load class in the record, Y4, is the same load class that was noted in an Operation Steel Tiger mission in South Vietnam the primary goal of which was defoliation.

This reporting directly corresponds to other Air Force archives documents from 1973 showing that the Civil Engineers had developed a standard operating procedure for the use of herbicide on Takhli to avoid misuse. By June 1973, the unit was waiting for more herbicides. Hence, the records suggest the movement of herbicides to and from Thailand was not exclusively associated with RANCH HAND missions and that herbicides were used throughout Thailand.

Despite this evidence, VA’s position is that RANCH HAND aircraft and herbicides were either temporarily staged, or never staged, on Thailand bases. Further documentation and sworn statements contradict that claim.

William Easterly was stationed throughout Vietnam and Thailand from 1966-1967 and 1969-1970. He was a chief gunner on UH-1P helicopters that provided gun cover for RANCH HAND aircraft. He stated that when the weather was bad, the crew would stay in Thailand at Ubon, NKP, or Udorn. He stated, “back at our base, we would get buckets of Agent Orange and fill pump fire extinguishers with AO [Agent Orange] so we could spray around our com area.”

Because the spraying equipment on RANCH HAND aircraft and the barrels containing herbicides were known to leak, the risk of exposure throughout the flight lines as well as storage areas on Thailand bases was significant. John Scott, an Airman stationed at Ubon from 1969 to 1972, stated that he assisted in loading barrels of Agent Orange onto C-123s during the first part of his tour. He also noted in his sworn statement that the barrels “were leaking all the time” and the herbicide got all over his uniform and hands.

In Ubon veteran Ronald Switzer’s appeal to the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA), he asserted that he was a material handler of Agent Orange during his time at Ubon from 1968 to 1969. He, too, stated that the barrels often leaked. Leakage from “empty” herbicide barrels was also noted because it was difficult to drain the last two or three gallons. The color distortion caused by leaking barrels containing herbicides is noted in pictures of herbicides stored on Johnston Atoll. The herbicides stored on Johnston Island were burned at sea in approximately 1977.

3. The historical record reveals substantial herbicide use on bases in Thailand.

Although VA recognizes “there was significant use of herbicides” at numerous Thailand military bases, it only recently granted Thailand veterans the presumption of exposure afforded to Vietnam veterans.

Due to the density and high growth rate of tropical vegetation in Thailand, the military used herbicides because mowing was seen as labor intensive and ineffective. Furthermore, there are several reference reports admitting herbicide use throughout bases in Thailand. Herbicides were used to control vegetation in Thailand’s tropical environment. More specifically, herbicides were used to improve visual observation of the base perimeter.

Due to attacks on Thailand bases, military leaders ordered the use of herbicides. In a 56th Special Operations Wing memo with the subject “Lessons Learned from the Attack on Udorn, 26 Jul 68,” the Deputy Commander of the 7/13th Air Force ordered base commanders in Thailand to “review base defense plan with an eye to covering critical areas which are adjacent to the perimeter.” As a result, defense surveys and reassessments were conducted throughout Thailand, including one survey conducted from June 23 to 30 1969, at NKP, Udorn, Ubon, Korat, Takhli, and U-Tapao.

Regarding base defense, the survey stated:

A continuing vegetation control program is required for cleared areas under and between perimeter security fences. The area between the fences is intended to be used as a no-man’s land with additional detection and deterrent devices such as trip flares, TSSE, tangle-foot, etc. being employed within. In view of the above, a mowing operation for vegetation control will be impossible. As a result, a conscientiously controlled program of vegetation control through the use of herbicides must be applied. Application of herbicides must be directed toward retarding growth to provide a cleared area.

Because of ongoing security concerns, Air Force leadership ordered the use of additional herbicides. Several documents demonstrate that Agents Orange and Blue were present in Thailand. For example, 28,000 gallons of herbicides were airlifted by two C-130s from Phu Cat Airbase in Vietnam to Udorn prior to some of the RANCH HAND missions later launched from Udorn to targets in Laos from February 2 to 7, 1969. However, per the 1971 CHECO Report, only 7,000 gallons of this herbicide, mostly Agent Orange, were dispensed in Laos. That leaves 21,000 gallons of herbicide unaccounted for with their last known location in Thailand. This directly coincides with Air Force documents stating that defoliation operations around the Udorn perimeter occurred during this period. It stands to reason that this remaining herbicide was used at other bases since 21,000 gallons was far more than necessary for a single base. Hence, herbicides including Agent Orange were used in Thailand.

The prevalence of herbicide use in Thailand is further demonstrated by the embassy’s approval of the use of herbicides on several occasions. In 1972, vegetation control on Korat was regarded as a serious issue because dense growth provided the enemy with the opportunity to access the KC-135 parking ramp. As a result, the embassy approved the use of herbicides. Additionally, the 1973 CHECO Report states that soil sterilization and herbicide use was approved by the embassy in 1969 in accordance with the Rules.

These admissions correlate with sworn statements provided by several Airmen. Mr. George Collins was assigned to the Aero Space Ground Equipment (AGE) unit in U-Tapao for seven months beginning in 1969 and ending in 1970. He wrote in a sworn statement that he was twice assigned the task of “diagnosing and repairing a Buffalo Turbine fogger/sprayer unit which sprayed the base consistently for insects and defoliated the base perimeter and other areas on the base.” He witnessed drums with orange, blue, or white bands being stored in a shed at the AGE facility surrounded by defoliated soil. His statements corroborate documentation demonstrating the use of herbicides on U-Tapao in 1971 and 1972.

Historical reports establish that a squadron in 1971 “began spraying chemical herbicides on the troublesome plants.” In 1972, the leadership at U-Tapao sought to “expand use of herbicides” in clearing 100 feet from the perimeter fence and invoking an “aggressive program on vegetation control.” Together, the Airman’s statement and historical reports demonstrate consistent use of herbicides in which the Air Force utilized internal equipment to accomplish defoliation.

In Command Sergeant Major (Ret.) Kenneth Witkin’s statement, he attested to observing Agent Orange being sprayed around the barracks at Udorn in 1970-1971. This coincides with documentation demonstrating that Major George Norwood addressed the need for strong vegetation control and that the Base Civil Engineers had been requested specifically for vegetation control on Udorn in 1971.

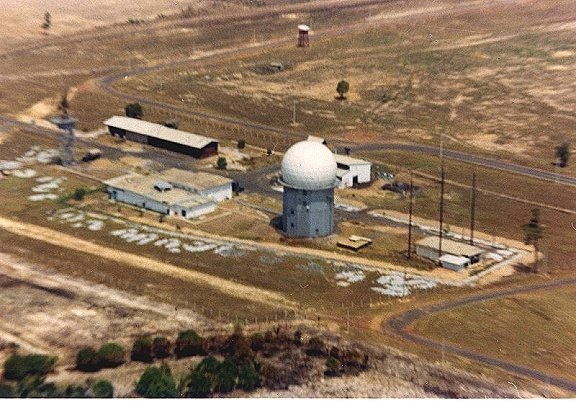

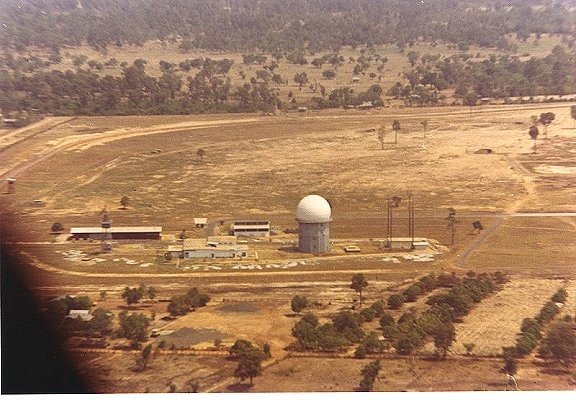

In his appeal to the Board of Veterans’ Appeals, Thailand veteran Ronald Switzer stated he was a material handler of Agent Orange and that after the 1969 attack on Ubon, the perimeter was pushed back and the “trees lost their foliage.” This correlates to documents showing the recommended use of herbicides in 1969 and their subsequent use in 1970, 1971 and 1973. Photographs of Ubon’s perimeter demonstrate it was pushed back and that there was a lack of foliage between the old and new perimeter.

Thailand veteran Michael Williams, who was stationed at Ubon from May 1969 to May 1970, asserted that he was assigned to a detail that involved defoliating the perimeter of the base. During the detail, he used defoliants that were contained in 55-gallon drums with orange stripes. Although he worked on the detail for 10 days, he stated that the detail continued for the rest of his time there. This matches documentation indicating herbicide use at and after that time.

The use of herbicides on NKP was noted in the 1973 CHECO report and in a soldier’s sworn statement. Thailand veteran Wayne Hogstad was stationed at NKP from April 1967 to April 1968 and was assigned to the police squadron. In Mr. Hogstad’s statement, he said that he observed a C-123 aircraft mounted with spray equipment next to barrels with orange stripes. He reported that he took time “to ride with a mobile unit Security Alert Team around NKP bases perimeters, [and] while going along the east perimeter a crew from civil engineering with a truck with a tank” sprayed what Mr. Hogstad believed to be Agent Orange. His statement aligns with the CHECO report, which notes that “heavy use of herbicides kept the growth under control in the fenced areas.” Moreover, Mr. Hogstad’s statement correlates with a historical record showing a request dated October 11, 1967, sought “six C-123 herbicide aircraft and 60 personnel to operate from [NKP] for a 15-day period.”

There are several additional pieces of evidence indicating that herbicides were used throughout Southeast Asia. The article “Viet Cong – Right or Wrong,” published in the National Guardsman in 1966, notes the Defense Department’s Advance Research Project Agency was moving forward with defoliant improvement projects in Thailand. This suggests that the defoliant improvement projects occurred after the herbicide testing (1964-1965). In turn, this supports veterans’ statements regarding the use of herbicide to clear bases in Thailand during this period. Mr. Dennis Oliver, who was stationed in Thailand from 1966-1967, stated that during his assignment to the base’s munition storage area, he witnessed 55-gallon drums being stored near the revetments and observed barren land throughout the perimeter and base.

The author of a 1982 article published in the Journal of Legal Medicine, titled “Agent Orange: Government Responsibility for Military Use of Phenoxy Herbicides,” states that “[e]very American who served in Southeast Asia was potentially exposed to Agent Orange, as the herbicide was used to clear areas before construction and to defoliate compound perimeters, landing zones, and fires bases.” For support, the author cites to an appendix to the 1979 hearing on Senate Bills 741 and 196. During the Committee hearing on S.B. 741 and S.B. 196, Congress considered perimeter spraying. Similar to the Air Force unit histories in Thailand, the 1979 hearing noted that herbicides were used around bases in order to maintain base security.

RANCH HAND was also not prohibited from herbicide spray missions in Thailand. In November 1969, the NKP Commander requested RANCH HAND assistance to defoliate the ordnance drop area. In his request, the Commander stated: “Application must be by air because area is overgrown and ground application would be extremely dangerous due to live munitions in the area.”

4. The Air Force developed a standard for herbicide use on Thailand bases

In order to create a uniform standard for the use of herbicides, military leadership established annual training and standard operating procedures. Annual training was conducted on Takhli from March 17 to 21, 1969, and July 13 to 16, 1970, with representatives from all Thailand bases. The 355th Civil Engineer Squadron and Pacific Air Force (PACAF) Command Agronomist sponsored the training. The training is an indicator that Air Force leadership took a cohesive approach regarding the application of herbicides on Thailand bases. On the herbicide school application, the listed purpose of the training was to “train and certify Thailand based personnel who will be handling herbicides for chemical vegetation control” and “train personnel on the use, application, dangers and safe handling of herbicides.”

The class consisted of twelve non-commissioned officers. Moreover, the application stated that select personnel would receive “their own copy of the herbicide manual.” Although the current whereabouts of the herbicide manual are unknown, the publication of such a manual demonstrates the regular use of herbicides throughout Thailand. As Mr. Raymond Gross, a PACAF agronomist, conducted the training, the herbicide manual was most likely employed throughout Southeast Asia.

This notion is further strengthened by the fact that the civil engineers developed a standard operating procedure (SOP) specifically for the disposal of herbicides due to fear that indiscriminate use of herbicide could be a source of pollution. The Air Force leadership argued that adherence to the SOP “should eliminate any misuse of herbicide application” on Takhli. This statement indicates that misuse of herbicides by service members led to the necessity of establishing an SOP. It is also another indicator that herbicide use was prevalent and supports statements from Airmen regarding the use of herbicides throughout Thailand.

Command Sergeant Major Kenneth Witkin stated that grounds personnel informed him they were using Agent Orange when he observed them spraying around barracks. Technical Sergeant William L. Easterly stated that RANCH HAND crew would use Agent Orange around their personnel area because they were not aware of the herbicide’s harmful effects. Although the SOP is not available or remains classified, the development and enforcement of the SOP highlights the prevalence of herbicide use and the concern of misuse on Thailand bases.

C. VA should presume exposure to herbicide agents for all Thailand veterans.

1. Thailand veterans were exposed to the same agents as Vietnam veterans.

Before the PACT Act was enacted on August 10, 2022, VA’s application of its Thailand perimeter policy only conceded exposure for service members with a security-related military occupational specialty (MOS), such as military police, who conducted foot patrols at the perimeter. In such a strict application, VA arbitrarily ignored its own policy of conceding herbicide exposure for veterans who served near the perimeter.

For example, many veterans on or near aircraft or near the barrels containing herbicides were exposed to the same risks as those conducting foot patrols. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Bailey, a member of RANCH HAND, noted that the pressurized aerial spraying tanks would leak herbicides inside the aircraft. Aircraft mechanic George Collins testified in a sworn statement that he worked on a RANCH HAND aircraft after it made an emergency landing in U-Tapao. While attempting to fix the aircraft, he was forced to kneel in the Agent Orange that covered the floor.

Leaking barrels also directly exposed service members to herbicides. Moreover, those members assigned to disperse herbicides by truck-mounted or backpack systems would certainly have been exposed. Yet VA’s past policy application eliminated even these veterans from receiving benefits based on their exposure to herbicide agents.

In James Trapp’s affidavit, he stated that during his assignment in Takhli’s warehouse, he saw barrels labeled 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D. Additionally, he stated the barrels “had white destination labels signifying they were for the 315th A/C Sq.” Historical Air Force documents from the 315th Air Division verify that 28,000 gallons (approximately 509 barrels) of Agents Orange and Blue were airlifted from Phu Cat, Vietnam, to Udorn in February 1969. This shows a robust relationship between the 315th Air Division and the movement of herbicides.

It is imperative to note that sworn statements of Airmen referenced throughout this report predate the Air Force Historical Research Agency discovering and/or releasing documents showing movement of herbicides from Vietnam to Thailand. This significantly enhances the credibility of these statements by confirming the veterans knew exactly to what they were exposed all along even though the government continued to deny the exposure.

National Archives records also reveal that herbicides were delivered to Takhli on April 7, 1973. Interestingly, this was after all aerial herbicide spray missions in Vietnam had ceased. This delivery would have resulted in the exposure of the aircraft crew; the loading, unloading, and storage crew; the crew involved in spraying the herbicides; and the service members in and around the sprayed areas.

Service members were also exposed to herbicides while constructing the perimeter. In Sidney Chancellor’s sworn statement, he noted that his duties in an engineer unit from June 1967 to November 1968 included spraying herbicides along NKP’s perimeter so that a fence could be installed. Mr. Chancellor reported, “[c]hemicals were stored in containers with orange stripes and we mixed the chemical with diesel fuel and loaded the mixture into a large tank mounted trailer that was pulled by an air compressor truck to spray the materials.” This coincides with an historical document dated December 1968 that provided an update on NKP’s fence and perimeter security and stated “grubbing [removal of trees and shrups] is complete for the southeast corner of the base and west perimeter, and approximately 50% complete for the north perimeter.” Hence, evidence suggests that airmen conducting construction around the perimeter were exposed to herbicides.

Due to the concerns over the integrity of studies completed for VA, the scientific community created a unified response rebutting the reasoning behind VA’s policies. Jeanne Stellman, an Agent Orange expert at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, and Fred Berman, the director of the Oregon Health and Science University’s CROET Toxicology Information Center, along with 14 other doctors, toxicologists, and environmental scientists, signed a letter in November 2012 that refutes VA’s “boots on the ground” approach to Agent Orange exposure. The letter addresses the scientific shortcomings and erroneous assumptions of VA’s position by noting, “skin absorption is a primary occupational route of exposure for dioxin-contaminated pesticides.”

Daily life on Thailand bases also exposed service members to herbicide agents. VA’s previous requirement that Thailand veterans must prove their duty position entailed working on the perimeter was unreasonable. U.S. Army Manual 3-3 (dated 1971) advises that a 500-meter buffer zone must be maintained to avoid damage caused by drifts while ground spraying herbicides. The distance between base perimeters and other base activities was normally well below 500 meters. Soldiers lived, worked, and conducted recreational activities near the perimeter and in areas well within the 500-meter drift zone. On Korat, for example, the physical training area and Non-Commissioned Officer building were located within the drift zone, and living quarters were only meters away from the perimeter.

Moreover, VA’s previous position that herbicides were only used along the perimeters is contradicted by documented evidence and sworn statements. When addressing the adequacy of facility security, official documents state that herbicides were applied to the “fenced in area around the ammo storage, facility, around all perimeter guard towers, and the areas around runway overrun lights.” The 1973 CHECO report also states that herbicides were “used on areas within the perimeter.” (Emphasis added.) Because service members were exposed to herbicides that were used inside the base, not just at the base perimeter, veterans who served in Thailand should not have to prove that their duties required them to be near the perimeter.

Several veterans’ statements also indicate herbicides were used within the perimeters of the bases. Mr. Collins stated there were several defoliated areas within U-Tapao including around the Aero Space Ground Equipment (AGE) facility, the baseball fields, and the viewing area for the “Bob Hope Christmas Show.” After the attack on U-Tapao, the 635th Security Police Squadron used herbicides to clear a 100-foot zone on both sides of the perimeter fencing.

Command Sergeant Major Witkin stated that he “personally observed Udorn-based grounds personnel often spraying herbicides, including Agent Orange, on the vegetation located in and around the barracks areas and on the base perimeter.” He stated the personnel spraying around the barracks told him the herbicide was Agent Orange.

Stephen Pippenger, a dog handler stationed at Udorn from September 1968 to October 1969, stated that he observed Agent Orange being loaded onto the C-123 aircraft. He also saw an aircraft spray the kennel area, and he remembers vegetation in that area dying shortly thereafter. Notably, Mr. Pippenger’s statement and the time period in which he served at Udorn coincide with official records of the delivery of 28,000 gallons of Agents Orange and Blue to Udorn in 1969 and the use of some of those herbicides by C-123 aircraft.

2. In Thailand cases, VA faces the same challenges of determining exposure details as with Vietnam veterans.

A key fact leading to presumptive herbicide agent exposure for Vietnam veterans was that herbicide records were incomplete, making it impossible to determine who was actually exposed. As noted in a 1986 report to the White House, only two percent of military records were preserved in the National Archives, and herbicide records were not regarded as a priority for retention.

In a 1986 memorandum from an Agent Orange Working Group, the panel concluded that herbicide records were incomplete and that a “large proportion of firebase perimeter spray operations were never recorded.” In a 1981 draft statement, James Stockdale, the Deputy Under Secretary for Intergovernmental Affairs, noted that documentation regarding perimeter spraying was poor and that “less than 5 percent of all helicopter spray missions were recorded on Herbs tapes.”

The government’s inability to identify exposed veterans led Congress to afford veterans the benefit of the doubt as to whether they were exposed by granting the presumption of exposure to all veterans who served in Vietnam. The 1986 Scientific Feasibility of Agent Orange Ground Troop Study noted that the group could not gain a clear indication from exposed verses non-exposed veterans because the records were incomplete. Further, in a 1986 transcript of the Ad Hoc Subcommittee Agent Orange panel, the committee noted that the potential of exposure at base camps “would appear to be considerable because of the regularity of spraying.” Moreover, the subcommittee determined that “levels of exposure are likely higher from exposure in the camps than from Ranch [H]and spraying.”

Before Congress granted the presumption of exposure, government records showed that determining the level of exposure was impossible. The Agent Orange litigation team relied heavily on perimeter spraying, which is noted in its 1984 files. The team also focused on exposure resulting from procuring, shipping, storing, or loading herbicides.

In Dr. Alvin Young’s working paper draft of suggested criteria for determining levels of herbicide exposure, he noted that groups exposed to associated dioxin contaminant were personnel assigned to support functions, to include:

Personnel that sprayed herbicides using helicopters or ground application equipment; personnel that may have delivered the herbicide to the unit performing the defoliation missions; aircraft mechanics who were specialized and occasionally provided support to RANCH HAND aircrafts.

Several sworn statements and unit histories show there are numerous veterans who served in Thailand and would have met Dr. Young’s criteria. He recognized in a draft report that the number of military personnel exposed is unknown because “most military bases had vehicle-mounted and back-spray units available for use in routine vegetation control.” Dr. Young’s documents indicate that herbicides, including Agent Orange and its counterparts, were used for routine vegetation control programs.

The similar exposure situations between Vietnam and Thailand merit equal protection, to include the presumption of exposure, for all Vietnam-era veterans who served in Thailand.

3. VA’s illusory distinction between “commercial” and “tactical” herbicides is unlawful and arbitrary.

VA has constructed an arbitrary distinction between “tactical” and “commercial” herbicides. They routinely use this “distinction” as justification for denying Thailand exposure claims. But historical documentation shows no evidence that the military made any distinction between “commercial” and “tactical” herbicides at the time of the Vietnam War. In fact, the distinction is notably absent from records until 2009 when VA published a “Memorandum for the Record” regarding herbicide use in Thailand during the Vietnam Era.

The “Memorandum for the Record,” which VA often cites in these cases, is outdated, contains erroneous and misleading statements, and was never intended for perimeter policy cases. Yet, VA has used this Memorandum and the so-called distinction between “commercial” and “tactical” herbicides to deny thousands of herbicide-related disability claims by Vietnam-era Thailand veterans.

Until 2009, VA made no distinction between “commercial” and “tactical” herbicides. The term “commercial” herbicide is notably absent from Air Force archive documentation, including the 1973 CHECO report which specifically states that herbicides used in Thailand had to undergo the same embassy approval process as herbicides used in Vietnam. The term “commercial” in reference to herbicides is equally absent from VA’s internal policies and procedures and from federal statutes and regulations. The term is used only in the Memorandum for the Record and in individual cases wherein VA uses the distinction to deny benefits.

In its original conception, the Memorandum for the Record was never intended to apply to all Thailand exposure claims. VA created the Memorandum as part of Fast Letter 09-20. Fast Letter 09-20 dealt exclusively with Haas-related claims from Thailand veterans that had been stayed. Fast Letter 09-20 states in part:

The stay affected a large number of veteran claimants with service in Thailand during the Vietnam era. Thailand was a staging area for aircraft missions over Vietnam, and many veterans who assisted with these missions received the Vietnam Service Medal (VSM) for their support of the war effort. Disability claims from those veterans who received the VSM for Thailand service, but who did not set foot in the country of Vietnam, were placed under the Haas stay.

Once VA lifted the stay, these claims still required adjudication. However, these stayed claims did not involve claims due to herbicide exposure around Thailand bases or their perimeters. The Memorandum was an attachment to FL 09-20 which was aimed at assisting Regional Offices in completing the adjudication of the stayed Haas-related claims.

In addition to being inapplicable, the Memorandum for the Record is outdated. VA’s policy on herbicide exposure around Thailand base perimeters did not even exist when FL 09-20 was issued in 2009. The Thailand base perimeter policy was not issued until May 2010, when it was introduced in a Compensation & Pension Service Bulletin. The M21-1 Adjudication Procedures Manual was later amended to incorporate the perimeter policy, but the Memorandum was never corrected, amended, or removed from the Manual and VA continues to apply the outdated Memorandum to Thailand base perimeter claims.

Furthermore, the Memorandum for the Record contains erroneous and misleading statements. In the Memorandum, VA states that the 1973 CHECO Report “does indicate sporadic use of non-tactical (commercial) herbicides within fenced perimeters.” This statement is misleading because the CHECO Report never distinguishes between tactical and commercial herbicides use—it refers only to “herbicides.”

VA’s distinction between “tactical” and “commercial” herbicides has no basis in federal statutes or regulations. The statute that defines “herbicide agent” focuses solely on the chemical agents contained in the herbicides used in Vietnam. 38 C.F.R. § 3.307 (a)(6)(i) defines an “herbicide agent” as “a chemical in an herbicide used in support of the United States and allied military operations in the Republic of Vietnam . . . specifically: 2,4-D; 2,4,5-T and its contaminant TCDD; cacodylic acid; and picloram.” (Emphasis added.) A substance containing any of these five compounds is an “herbicide agent” as a matter of law, regardless of its purpose or name brand. The distinction between a tactical herbicide and a commercial herbicide has no legal or factual significance.

During the Vietnam Era, the military made no distinction between “commercial” and “tactical” agents in their own supply system. In approximately September 1958, 2,4,5-T was adopted for use by the government under Specification O-H-210 and Federal Stock Number (FSN) 6840-577-4201 for a 55-gallon drum, and then later under FSN 6840-616-9159 for a five-gallon can. Chemical Corps described these products as “expandable supply items to be available to all users,” meaning they “were meant for use by facility engineers as an herbicide for grounds keeping (i.e., brush and weed control).”

Agents Blue, White, and Orange all known to contain chemical agents outlined in § 3.307, were also available in the federal supply system. In the early 1960s, military personnel had access to Agents Pink, Purple, and Green, most of which were undiluted versions of 2,4,5-T and therefore contained even higher levels of TCDD than Agent Orange. VA clearly cannot support its long-held position that “routine base maintenance activities” were only performed by use of “commercial” herbicides that could not satisfy the § 3.307 requirements. VA’s distinction between tactical and commercial herbicides is therefore misguided, arbitrary, and contrary to law.

The government made no distinction between these herbicides in the 1970s and 1980s either. In fact, they specifically pointed out that defoliants VA now labels as “tactical” were commercially available. In response to a 1971-72 Congressional record, an Air Force consultant wrote, “[t]he Air Force does not and has not used any defoliants that are not in general use in this country.” Later, in the 1980s, the government did indeed ban the use of all 2,4,5-T based herbicides for the same reasons it previously stopped the use of Agent Orange (a 2,4,5-T based herbicide) in Vietnam—contamination with 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, or TCDD.”

4. PACT Act establishes presumptive service connection for Thailand veterans.

As stated above, prior to the passage of the PACT Act, veterans could only be eligible for presumptive service connection if they served near the perimeter of specific bases. This often meant that the veteran needed to prove that their MOS required them to be near the perimeter of the base.

As of the enactment of the PACT Act on August 10, 2022, veterans who served in Thailand are eligible for presumptive service connection, regardless of their MOS or where on the base they were located.

VA now recognizes that any servicemember with active military naval, air, or space service who served in Thailand, at any U.S. or Thai base, between January 9, 1962 and June 30, 1976 were likely exposed to Agent Orange. VA has established presumptive service connection for these veterans, meaning that VA will assume exposure to Agent Orange if veterans can prove that they served in Thailand, at any US or Thai base, between January 9, 1962 and June 30, 1976.

To learn more about current Agent Orange presumptions for Thailand, please visit CCK’s PACT Act breakdown.

Thailand Agent Orange Claim Denials

If your VA disability claim related to exposure to Agent Orange in Thailand has been denied, we may be able to help you. The legal team at Chisholm Chisholm & Kilpatrick LTD has done extensive research on the use of herbicides in Thailand during the Vietnam War. Contact our office today for a free consultation with a member of our team.

Share this Post